Healthier Eating From Island ‘Food Forests’

Across North America, the coronavirus pandemic fueled new interest in raising edible plants. Yet well before the pandemic, communities on Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands have been quietly planting forests—for food.

In Victoria, a thriving food forest has been operating in Banfield Park since 2006. In Duncan, the non-profit Cowichan Green Community began work on a food forest in 2012. On Galiano Island, the Galiano Conservancy Association operates two forest gardens. The goal of these forest projects is to improve food security for residents and enhance the quality of food available to the community.

What is a food forest?

“A food forest is a manmade ecosystem that mimics the natural world,” explains Laura Boyd-Clowes, supervisor at KinPark Youth Urban Farm, one of the forest garden projects that Cowichan Green Community operates.

Unlike the neat rows of a conventional garden, a food forest (or forest garden) is typically designed vertically, with taller fruit- or nut-bearing trees, lower berry-producing shrubs and combinations of greens, herbs and vegetables at ground level. This layered approach enables a forest to produce food year-round in a compact urban environment.

Some food forests are run like community gardens, where residents can pick what they want. Others operate like farm businesses, selling their products through farm stands or to local restaurants

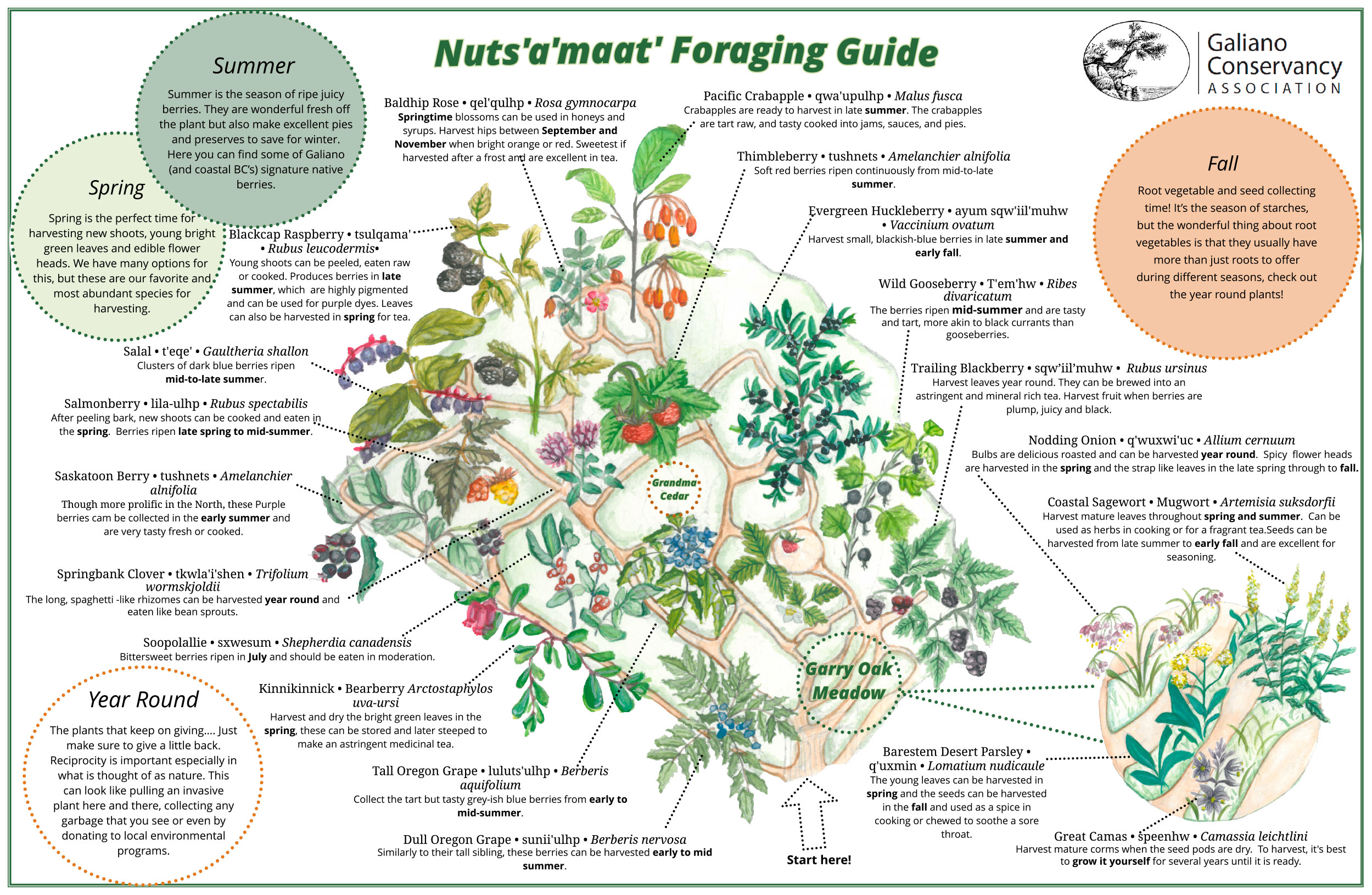

Infographic used with permission by the Galiano Conservancy. Map designed & illustrated by Sylvie Hawkes. Names listed in the Hul'qumi'num language.

Victoria’s Banfield Commons

In the early 2000s, Patti Parkhouse and several other Victoria West residents organized the Vic West Food Security Collective, where Parkhouse is now the project coordinator. To make fresh food more accessible to residents and create a village gathering space, they decided to plant a food forest in the neighbourhood’s Banfield Park.

The volunteer-managed Banfield Commons now produces cherries, figs, goji berries, autumn olives (a berry-bearing shrub), cardoons, nettles, greens, herbs and more, which neighbours can harvest and eat. Parkhouse says they try to choose plants serving multiple functions. A boxwood hedge looks nice but doesn’t produce anything edible, she explains, while native huckleberry, an alternative green shrub, grows berries that are excellent for jam.

Duncan’s Food Forests

The Cowichan Green Community (CGC) transformed an urban lawn into the one-acre KinPark Youth Urban Farm in 2012, planting dozens of trees, berry bushes and herbs. At this food forest, community youth learn to grow food and operate food businesses.

In downtown Duncan, the CGC constructed the larger Community Urban Food Forest in 2014 on reclaimed land around The Station, a complex of green-focused businesses. Apples, mulberries, cherries, grapes, strawberries, mint, even kiwi all grow here in the city centre, where community members can gather fruit or simply enjoy the space.

“When you create a beautiful welcoming space, people want to be there,” Boyd-Clowes says, which at the same time can create challenges, particularly if people congregate late at night. “We’re horticulturists and activists, not police or social workers. But sometimes we struggle with having to police the space.”

Forest Gardens on Galiano Island

The Galiano Conservancy Association designed a forest garden in 2015 to mimic the natural forest system with layers of trees and plants, explains Cedana Bourne, the Conservancy’s agriculture coordinator. The garden is structured around raised hugelkultur beds, which use decaying wood to provide plants with nutrients and moisture.

The Conservancy planted fruit and nut trees, bulbs (such as garlic and onions,) a variety of greens (including arugula, lettuces, and kale), fennel, carrots, daikon and other vegetables, and both culinary and medicinal herbs, some of which they harvest to make tea. The forest garden supplies much of this produce to island restaurants. Garden staff also sell teas and plants to the public, offer education programs for youth and adults, and coordinate volunteers who help maintain the garden.

Working with members of the Penelakut First Nation, the Conservancy launched a second food forest, Nuts’a’maat Forage Forest, in 2017, on land that had previously been logged. More than 50 species of edible and medicinal native plants grow in this regenerating ecosystem. While this forest is used primarily for educational activities, the Conservancy publishes a foraging guide and allows the public to gather food here.

So you want to start a food forest?

Before starting a food forest, Bourne advises that “the most important thing is figuring out what your community needs.” Will its primary purpose be to feed the hungry, allow people to grow food or provide education?

You also need time to determine what would grow best on the site and consider the layout, soil composition, available water and amount of sun and shade. “Native plants are obviously well-suited to an area,” Bourne says, and planting diverse layers and types of crops acts as a safety net.

Food forests are about community, says Vic West’s Parkhouse. During this pandemic year, many more volunteers have turned up at Banfield Commons, getting outside while contributing to the neighbourhood.

Food forestry is critical in fighting climate change, adds Boyd-Clowes, who points out more delicious benefits as well: “I can’t even describe the excitement of harvesting mushrooms in the middle of the city.”