From Catch to Can at St. Jean's

Canned fish may not be your idea of epicurean fare, but a visit to a traditionally-minded Island cannery that has outlasted all of its competitors could change your mind. Tucked away in an industrial part of the southern Vancouver Island city of Nanaimo, St. Jean’s Cannery and Smokehouse is one of only two commercial seafood canneries still operating in British Columbia and the only one that processes wild-caught Pacific salmon and tuna.

Salmon canning was once big business in British Columbia. In the early 1900s, scores of canneries dotted the province’s coastline, pumping out product for domestic and international markets. But as it became easier to get fresh fish to distant markets, demand for the processed version dwindled and one by one, B.C.’s canneries were shuttered. After the Canadian Fishing Company (Canfisco) eliminated the canning line at its Prince Rupert plant on the North Coast in 2015, St. Jean’s stood alone in a once-crowded field.

So how did St. Jean’s manage to endure? Steve Hughes, the current company president, credits the farsightedness of founder Armand St. Jean, and his son and successor, Gerard. In the industry’s early days, almost everything was done by hand, from manufacturing the cans to gutting, scaling, cutting and packing the fish. But as the 20th century progressed, cannery owners increasingly turned to automation to speed up production and reduce labour costs. By the time Armand got into the business in 1961, butchering and can-filling machines were the norm. St. Jean’s, however, bucked the trend back then and still favours the personal touch.

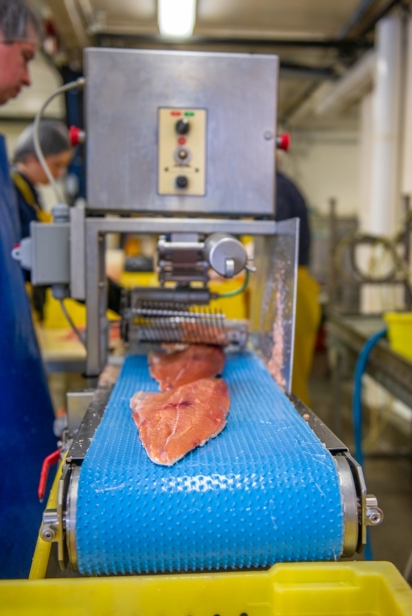

“We’re a hand-pack cannery,” Hughes explains, “so we’re a little bit more niche and that’s one of the reasons we’ve survived.” With the “high-volume canning” that used to be standard on the B.C. coast, and still is elsewhere, “there’s a machine that’s literally a piston jamming salmon into a can. What we do is select only the best stuff, cut out any bruises, anything like that, and place it in the can by hand. So, we’re obviously operating at a little bit lower volume than a giant piston could do, but we’re a high-end quality producer.”

As Hughes shows me around the maze of interconnected buildings that make up the St. Jean’s processing facilities, the care that goes into all of their products is evident. On the cutting line, half a dozen employees wield long-bladed knives, working in silence as they rapidly reduce whole fish to piles of glistening flesh under cleansing streams of ozonized water.

“Our cutters are highly skilled people,” Hughes tells me. “It takes several years to learn the job, so they tend to stay on for a long time.”

In the canning area, 10 women wearing blue hairnets and bright yellow aprons stand at high tables loaded with bins of raw tuna. With nimble, rubber-gloved fingers they deftly select pieces of fish and pop them into the open cans. Another worker wheels trays of filled cans across the room and loads them onto a conveyor apparatus. As they travel its length under a supervisor’s watchful eye, each can is seasoned with a dash of sea salt before its lid is dropped into place, vacuum-sealed and seamed. Finally, a brawny, pink-cheeked woman transfers the cans into a massive, steam-hissing retort pressure cooker.

While its persistence as a cannery sets St. Jean’s apart from other seafood processors, its product line includes much more than canned fish. In fact, that wasn’t even part of Armand St. Jean’s original vision. He began the business with oysters, which he smoked in his backyard smokehouse, packed into plastic bags and hand-sold to bar patrons around town. His “smudgies” proved so popular that he soon switched to packaging them in glass jars and then metal tins, using a hand-steamer unit. Within a few years, he had added oyster chowder and salmon to his list and moved from the family kitchen into a dedicated processing facility.

Smoked oysters are still a best-seller for St. Jean’s. “We ship them all over the world,” Hughes says, “because once you’ve had ours, you can never go back to anything else, so people get pretty addicted. We have campers pull in from Alberta and they’re loading up and going off for the summer with their cases of smoked oysters.”

When Armand retired in 1978, Gerard, who had been working as machine design engineer, took over. He remained at the helm for nearly four decades, a hands-on manager who wasn’t above scrubbing out fish totes when that was what needed to be done.

Four years ago, Gerard set St. Jean’s on a new course, selling controlling interest in the business to NCN Cannery, a limited partnership between five of the 14 Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations that call the western side of Vancouver Island home. “What appealed to Gerard,” Hughes says, was the promise of “continuity, a sense of still being Island-based and sharing the same values around trust and integrity.”

But it was also a ground-breaking decision, for although First Nations labour was critical to the flourishing of British Columbia’s canning industry, First Nations cannery ownership is almost unprecedented in British Columbia.

Larry Johnson is a member of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation and the president of NCN Cannery’s parent company, Nuu-chah-nulth Seafood. He says the Nuu-chah-nulth are “really happy and proud to own St. Jean’s,” and committed to carrying on Armand’s and Gerard’s vision. “We didn’t want to change anything. They’ve got a fantastic company here. We just want to build on the success.”

The proof that they’re doing just that is in the can.

Whether you’re stocking your pantry or packing for a picnic, you can buy St. Jean’s products from the cannery (242 Southside Dr., Nanaimo; open Monday to Friday, 9am – 4pm) or from gift stores and seasonal kiosks (full list at https://www.stjeans.com/contact-us/).

The St. Jean’s retail brand, Raincoast Trading, is available in many grocery stores (https://raincoasttrading.com/where-to-buy/).

Interested in taking a tour of the cannery? Email matt@stjeans.com.