The Culture of Aquaculture

We’re cruising through Clayoquot Sound, returning to Tofino after an idyllic day at Hot Springs Cove, when we start noticing the open net pens of the salmon farms in one sheltered bay after another. It’s a little jarring here amid the old growth forests and crystalline waters. This is, after all, a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, which people fought fiercely to protect during 1993’s War in the Woods. And fish farms, well, they don’t exactly have a great reputation when it comes to sustainability.

But is that reputation justified? Sometimes yes—and sometimes no. As our guide points out, “You’re not going to hear a lot of criticism of the fish farms around here. They employ a lot of people.”

And that’s the rub: when it comes to fish farms and sustainability, it’s all shades of grey. How do you even define sustainability? Is operating a fish farm worse than dredging the ocean floor? What about the owners who are trying to do things right? Are some types of aquaculture better than others? And, ultimately, what decisions should consumers be making at the grocery store?

Part of the Food Chain

“I don’t understand why some people think all fish farms are the devil. After all, we farm everything else,” says Warren Barr, owner and chef of Pluvio Restaurant + Rooms in Ucluelet. “Shutting them down is not the answer. Lean on the ones that are doing it to do it better.”

The truth is that most of the seafood consumed on the planet is farmed—and our food security depends on it.

“We’re now at a point in our shared human history where over 50% of our seafood is coming from aquaculture,” says Claire Dawson, the senior science lead for Ocean Wise Seafood, the global conservation program that originated with the Vancouver Aquarium. “The important thing to remember about aquaculture is we can’t live without it, but there is a massive spectrum when it comes to sustainability.”

Dawson suggests that we should think of aquaculture in the same terms we consider land-based farming. “Think of plant-based agriculture versus a steak,” she says, adding, “We don’t seek to demonize any one method of production. We try to give good information on what the best options might be. It’s not about saying ‘this is the only right way’ or ‘this is the only wrong way.’ A fish is not a fish is not an oyster is not a mussel. It’s all very contextual.”

Overfishing, Habitat Destruction, Wanton Waste

If you think wild-caught seafood is the better choice, well, think again.

We are, quite simply, overfishing our oceans. Global consumption of seafood has doubled since the 1970s. One-third of the world’s fish stocks are overfished. An estimated 40% of what is caught is discarded as bycatch, which refers to unwanted species, including dolphins and marine birds, that are scooped up in vast nets then tossed away. Some forms of commercial fishing, like dredging, also damage traditional spawning and breeding grounds, preventing future generations from being born.

Even our local wild-caught salmon has its issues. Barr hasn’t served it ever since he learned that the endangered resident killer whales in the southern Gulf Islands are dying in large part because their major food source, Chinook salmon, has been so drastically overfished.

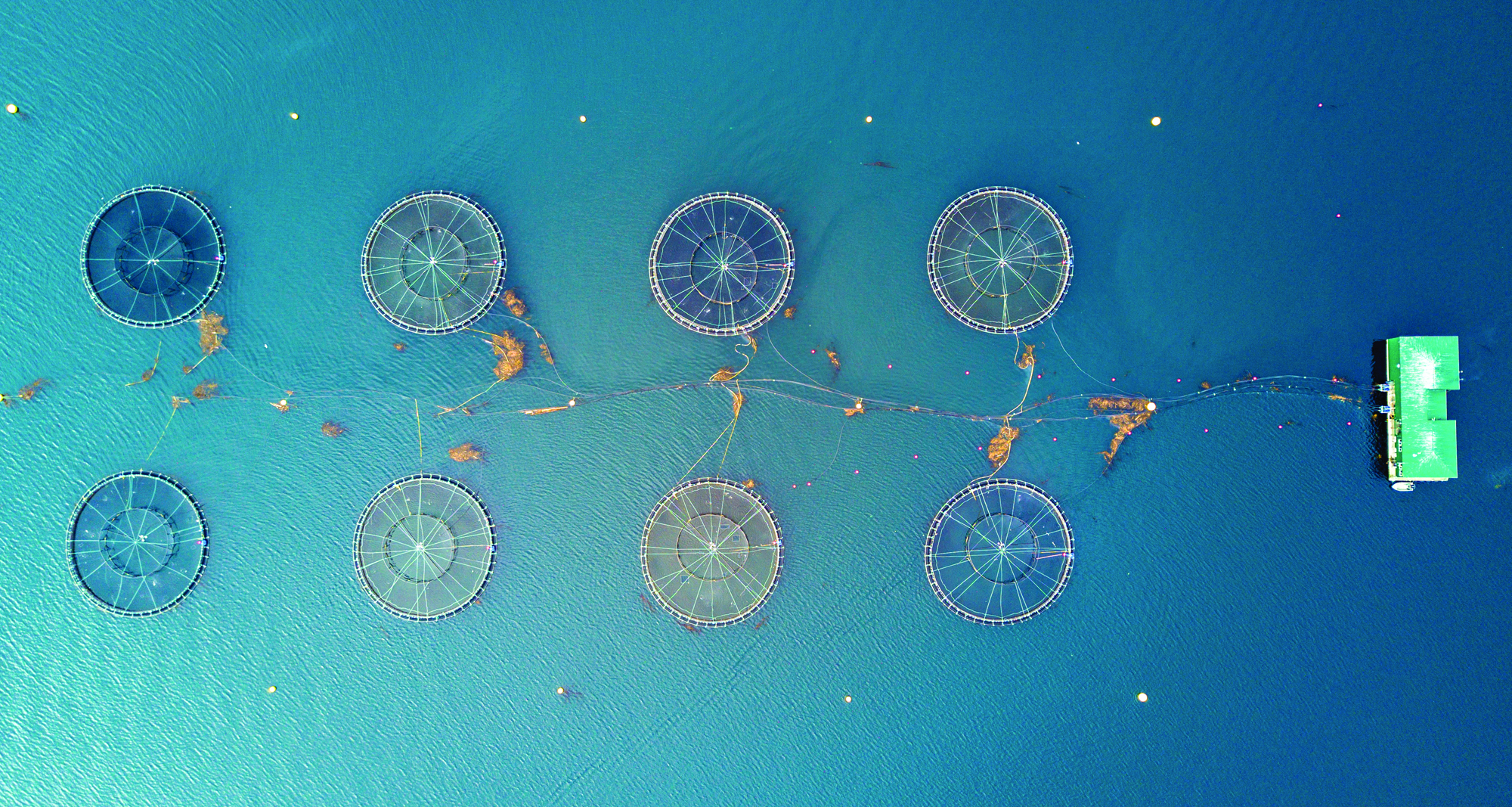

Open net fish farm

So how can fish farming be worse than this?

Easily. Open net pens are a problem because the fish are in direct contact with the surrounding ecosystem. The farms can release pollution from wastewater, cause potentially lethal infestations of parasites and dump excess amounts of antibiotics that could lead to antibiotic resistance in humans. Worse, almost all farmed salmon is non-native Atlantic salmon that can take over a wild population’s food or habitat. Some experts also believe escapees could interbreed with local species and produce less genetically fit offspring.

In other words, they could wipe out our native West Coast salmon.

That’s why Washington state banned open net farms in 2018 (to take effect in 2022), why almost every year sees a new petition to ban them in B.C. and why Ocean Wise doesn’t recommend any open net pen salmon farms on the coast.

Not all Aquaculture is Created Equal

Ocean Wise has, however, approved one open net sablefish farm: Gindara Sablefish in Kyuquot Sound, off the northwest coast of Vancouver Island. (It is a partnership with the Kyuquot-Checleseht First Nations, and it’s worth noting that some 20% of people employed by fish farms are Aboriginal.)

Gindara Sablefish

Gindara Sablefish

“Sablefish is a native species farmed in native waters. If they do escape, they are not an invasive species,” Dawson says. The farm doesn’t use antibiotics or pesticides and has low stocking densities so the fish have lots of room to swim and grow, which also minimizes their impact.

But that’s sablefish. So far, it’s believed that B.C.’s wild salmon won’t thrive in net pens. Creative Salmon, near Tofino, is proving differently. The company produces its own broodstock of native Chinook salmon, raises and harvests the fish locally and processes it right on the dock in Tofino. In 2013, it became the first salmon-farming company in North America to achieve organic certification.

Risk of escapees aside, the team at Ocean Wise judges the sustainability of aquaculture on two things: inputs, that is, feed; and outputs, as in waste, chemicals and antibiotics. Improvements have been made in both areas. Fish feed on other fish, and more of that feed is coming from sustainable sources. And where fish farms once emitted so much waste that the seabeds under them essentially became deserts, in B.C., more and more of them are noticeably reducing their impact on the surrounding areas.

“It’s getting more responsible overall,” Dawson says. “And globally the demand is for aquaculture to be responsible. Those companies who don’t start following this trend will ultimately get left behind.”

But there are other options besides salmon from open net farms.

The most sustainable species farmed in our waters are photosynthesizers (that is, seaweed) and filter feeders, which comprise shellfish such as oysters, clams, mussels and scallops. Farmed shellfish are hatched and grown in a lab, then placed in coastal areas to mature until they reach market size. They need no chemicals to help their growth and no feed, either—they live off excess nutrients already in the water column. As for waste, well, they actually clean the water.

The most sustainable species farmed in our waters are photosynthesizers (that is, seaweed) and filter feeders, which comprise shellfish such as oysters, clams, mussels and scallops. Farmed shellfish are hatched and grown in a lab, then placed in coastal areas to mature until they reach market size. They need no chemicals to help their growth and no feed, either—they live off excess nutrients already in the water column. As for waste, well, they actually clean the water.

Another good choice can be fin fish from land-based tanks such as Vancouver Island’s Kuterra Salmon. In B.C., tanks are closed systems that recirculate water. Any effluent is captured and, in some cases, used as fertilizer. And, of course, there is little to no risk of escapees.

The Best Choice for the Planet

Faced with all these choices, which ones should consumers make?

Start by informing yourself. Then shop at retailers that have good practices, and look for labels that identify sustainable options, such as Ocean Wise, Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and SeaChoice. And be prepared to have a conversation with your fishmonger. “The most important thing people can do is just start asking questions. ‘Where was your seafood caught?’ And then, ‘How was it caught? How was it raised?’” Dawson says.

The fact of the matter is, seafood farming is essential to feed the planet, now and tomorrow. We just need to do it better.

As Barr says, “I am generally on the side of the future. We need it. It’s not a matter of shutting them down. It’s a matter of supporting the guys who are doing it right.

One Fish, Two Fish, Farmed Fish, No Fish

Trying to decide on the most sustainable seafood choice to feed your family? Here are your options:

Shellfish

Almost all commercially sold B.C. shellfish is farmed in pristine coastal waters with virtually no inputs or outputs, and it is the most sustainable seafood product you’ll find, aside from seaweed.

Land-based recirculating tanks

Delicious salmon, char, steelhead trout and sturgeon are all raised in land-based tanks. Admittedly, tanks can be costly, high-maintenance operations, and if disease enters the system, the entire “crop” can be wiped out. But if the system is closed—as they are in B.C.—they have virtually no outputs and, of course, no risk of escapees.

Open net pens

Ocean Wise does not as yet consider fish raised in open net pens a sustainable choice. However, the organization notes that they have vastly improved in terms of the feed they use and how much waste they produce. Escapees, though, are still a risk, so the best choices here are from farms that raise native species, like Chinook salmon or sablefish.

Wild harvesting

Some wild-harvested seafood is sustainable. Some is not. Certain species should be considered off-limits because they are so overfished—bluefin tuna, for instance, or swordfish. Some fishing techniques (dredging, trawling, longline or pelagic net fishing) should raise red flags because they are linked to habitat destruction or have high levels of bycatch. And certain regions are more problematic than others because of habitat loss and other issues. Here in B.C., you can feel good about enjoying wild-caught albacore tuna, wild halibut, Dungeness crabs and spot prawns.

Local vs. Imported

When in doubt, choose local. It’s easier to trace provenance, demand accountability and support our neighbours, which is especially important as we climb back from the havoc wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic. Besides, the province, and especially Vancouver Island, offers some of the best, most sustainable seafood on the planet.

Be Informed

Most importantly, the best way to enjoy seafood that doesn’t damage the planet is to be a better-informed consumer. Do your research, know your sustainability certification criteria, read the labels, ask questions and demand better choices from your suppliers so we can enjoy the bounty of our waters for generations to come.