Hop to it!

Julia Nicholls pulls hop cones from long bines (not vines!) laid out on a table and tosses them into a bin. The sun sparkles overhead on this late summer morning as she and more than 50 volunteers bring in the harvest on Hope Bay Hop Farm on Pender Island in the balmy Gulf Islands.

“I come and work for free,” she says, “because I love to chat and catch up with my friends. This is like an old-fashioned barn raising.” Gregory, her husband, chimes in: “I love craft beer, and these hops are organic. We support island businesses and since we live just down the road from this farm, what could be more local?”

Some volunteers cut the long bines, which grow on tall 16-foot vertical wires, using long scissored poles. Others stack the vines next to tables where volunteers like Julia separate the cones—about the size and shape of fir cones—from the plants.

It’s a bucolic scene with the land sloping gently to a creek lined with trees laden with blushing red apples. Sheep graze on a nearby farm.

Richard Piskor, the farm’s owner and a retired University of Victoria physics professor, has been welcoming volunteer pickers since 2016. “This crowd has arrived in response to emails and word of mouth,” he says. “I don’t even have to use social media or advertising because people are upset if they miss this event.”

Helping out for free is a deep-rooted custom that pervades Pender and the rest of the Gulf Islands. “Almost everyone volunteers in some capacity,” says Gregory Nicholls. “It’s simply what we do.”

A Joyful Experience

The hop harvest resounds with constant joking and laughing. One woman wears a tiara made of a hop vine. Two friends decorate a fence with hop vines. All the while, gentle guitar music wafts over the orchard. Bill Heintz, a professional guitarist, insisted on coming and playing for free. “I’ve lived and performed in many places, but none has the spirit of Pender Island. It’s a privilege to play here. I love being part of this unique community.”

Many volunteers are essential because the hops must be picked in one day and the crop is too small for mechanized picking. As plastic bins are filled, they are carried to a van, which will transport them to the mid-afternoon ferry and then on to the Hoyne Brewery in Victoria where they will be made into Wolf Vine Ale.

Hops are a crucial element in beer making, imparting a bitterness that balances the sweet malt flavour. According to owner and brewmaster Sean Hoyne, “Using fresh [rather than dried or pelletized] hops yields unique flavours—brighter and more citrusy. The ale tastes like it’s from a farm. And Piskor farms organically, yielding a superior quality and taste.” As an additional benefit, the hops are cleaner without the pieces and leaves that come with machine picking.

Hop-growing in BC has had its challenges. In the early 1900s, southern British Columbia was the largest producer of hops in the British Commonwealth. But by the 1990s, hop-growing was having its last gasp. Then in 2007, a series of events destroyed hop plants around the world, coinciding with the rising popularity of microbreweries. A BC hop-growing renaissance followed.

In 2014, Richard Piskor joined the trend, planting 440 hop vines on his seven-acre farm. After some initial difficulties, the Cascade and Sterling hops now grow well—up to 25 cm per day! And Hoyne takes all his product.

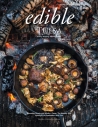

On this warm September day, hop picking stops at noon for lunch. Tables groan under fresh bread, salads, a popular jackfruit curry and homemade cookies. Best of all, Hoyne has supplied a generous array of craft brews, the bottles glistening with condensation. Chatter and laughter are replaced by the clatter of cutlery and clink of bottles.

Work restarts. By 2:30 pm, the Hoyne van is crammed full, the final bin is squeezed onto the passenger seat, and 500 pounds of hops depart for the ferry. Once at the brewery, they’ll be placed in a vat to begin a new batch of Wolf Vine Ale. The ale is seasonal, and come fall, the resulting 8,000 bottles will sell out quickly.