The Heart of the Hunter

In the backwoods of Vancouver Island is a man and a young girl. They kneel on a ridge, the morning sun warming their backs as it breaks across the horizon. Motionless, they stare at the field across from them, admiring the beauty of a buck wandering through the dewy grasses. The sounds of the songbirds and crickets fade away as the father nods to his daughter, who focusses intently down the sight of her firearm, every muscle tense, waiting for the perfect moment. A shot breaks the still morning, reverberating on the trees. The buck falls, the shot clean and true. The girl’s first hunt will feed their growing family for months to come.

It is a picture that can be imagined across the province; fathers, mothers, daughters and sons participating in a hunt. Humans have hunted since time immemorial, to consume, to clothe, to craft. It is a practice steeped in patience, humility and respect for those who recognize the solemnity of taking a life. Like Rick Janzen, who has been hunting to feed his family for over 40 years; like Benj Klassen, who took up hunting a decade ago to teach his children how to honour the meat on their plates; and like Dan Hayes, a professional chef who has eaten meat from only his own hunts for the past eight years to hold connection with his food.

Seeking connection

Janzen began hunting in his 20s, a practice he has continued for decades. For him, the justification behind hunting is two-fold. For one, feeding a family is expensive. “I lived in a rural area where game is plentiful, and it seemed logical to pursue a hobby that would put food on the table. It was a good investment,” he explains. The second reason is based on a desire to eat meat that has grown in its local, natural environment, where there is less chance of exposure to toxins and chemicals and can result in an all around "healthier" meat.

For Klassen, his interest in hunting began around the time he had his first child and he began questioning his relationship with meat. “Dissociation with meat is so strong these days,” he says. “But we want our kids to understand that this comes from an animal.” Now the father of four boys, Klassen is raising his children to have an honouring relationship with meat by including them in the hunting process, teaching them firearm safety, respect for laws and nature and how to properly process each part of the animal.

Connection to the life of the animal is the primary reason Hayes only eats meat from animals he has hunted. “Whenever I’m eating meat, 99% of the time, that animal died as a result of my bullet,” he says. He admits that, sometimes, it seems absurd (“how dare I choose an imported avocado over a local Vancouver Island chicken—the environmental impact of that is ridiculous”), but he so strongly believes in being fully connected to the meat that graces his plate.

“It’s a solemn occasion”

Janzen doesn’t take the life of an animal lightly. He recalls the first time he felt the grave weight of responsibility burden him when he hunted an animal and touched its lifeless yet warm body. “It’s a solemn occasion,” he says. “But every time you buy meat, someone had to do that for you. In a way, you’re more ethical as a hunter, more connected to the consumption of the animal.”

Klassen echoes these sentiments, using the word “humbling” to describe the hunting experience. “I don’t want that to ever fade or to become desensitized to it,” he says. After all, it's these feelings that make us human, adds Hayes: “When a pack of wolves start eating something alive, they don’t feel anything; they’re just acting on an urge to eat meat.” Recognizing and sitting with those difficult emotions during a hunt is an important part of respecting the life of the animal. “It’s disrespectful to not acknowledge it’s an animal,” Hayes insists. “I’m connected to it with complete and utter respect.”

Recognition and honour of the animal is the reason why many cultures have traditions around hunting that involve reverently acknowledging the life that’s been taken, says Hayes. The Inuit commonly offer seals a last drink after they’ve been pulled ashore, with the belief that their souls would then return to the sea. A European hunting tradition involves giving the hunted animal a last bite, by placing a small branch in the animal’s mouth and connecting the hunter with a similar sprig placed in their hat.

Janzen has kept parts of the animal as small mementos for particularly notable hunts, reminding him of the animal and keeping another part of it from waste. Hayes has, as well—including a rabbit’s foot hanging from his car’s rear view mirror that reminds him of the first animal he hunted with his daughter. But this brings up the topic of trophy hunting, and is it right or wrong as a meat hunter to take part of an animal and keep it as a tangible memory? Hayes suggests that perhaps the topic is less black-and-white than some might assume.

A merciful death

Honouring the animal’s life means also giving it a “good” death. Klassen notes that when compared with the type of death the animal will face in the wild, a hunter’s calculated bullet is likely the best death it could hope for. “Nature is so brutal. We come upon carcasses, and rarely are they in one piece,” he reflects. “As humans, we can give an animal a clean and simple death. It is merciful, truly.”

Klassen says that often, this means making the decision to forgo the shot when you’re not certain it will be a clean death, even when it means going home empty-handed after a long hunt. That’s the responsibility of being an ethical hunter, agrees Janzen. “We want to take the animal as cleanly and ethically as possible by minimizing pain and suffering.”

Ethical hunting doesn’t end the moment the shot is fired, either; it also encapsulates the idea of using the entire animal. “Make sure you use everything you can and honour what you’ve taken—not just choice meats,” Klassen says. Trim and bones can go to dogs, livestock and chickens, while tallow can be used in cooking, candles and soap. Klassen has previously donated a hide to an Indigenous group for traditional practices; Janzen uses deer hair for tying flies for fly fishing.

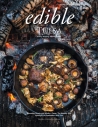

From hunted to plated

Part of ensuring the merit of the hunt is by being educated on how to efficiently and correctly handle the animal after its death. “From the moment the animal is down, you have got to be thinking food,” states Hayes. The meat must be cooled down as quickly as possible to keep the meat from spoiling—and thus causing the animal’s life to have been taken in vain. It’s why Janzen appreciates the ability to hunt close to home on Vancouver Island. “I can kill an animal and within an hour I have it home; from kill to skin off can be within three hours.”

“You’re not in a controlled facility in the wild,” Klassen says. “So it’s important to be educated on how to handle the animal.” He notes that hunters should know how to cool the meat, how to butcher the meat to make every pound count and how to store it for best longevity. Hayes adds that he finds it somewhat incredible how quickly a living animal becomes packages in the freezer. But he never loses that feeling of connection, even as he pulls out a package months after a hunt and recalls the animal it came from. “I remember that creature standing there, looking at me. You’re immediately re-connected to that day, to that moment.”